Episodes

-

CUAG has developed an audio description tour for "Drawing on Our History," designed for gallery visitors who are blind or who have low vision. It is intended for in-gallery use, but can also be used remotely.

"Drawing on Our History" is a celebration of CUAG’s 30th anniversary, bringing the works of eight contemporary artists (invited by past guest curators) into an open conversation with a wide-ranging group of historical and contemporary drawings selected from the University’s collection and made by Canadian and international artists.

The tour provides an overall description of the exhibition, and descriptions of ten works from the CUAG collection, including the newest acquisition, “Medusa” by Ed Pien. It also features descriptions and interviews with three of the invited contemporary artists: Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona, Mélanie Meyers and Marigold Santos.

In gallery, there are tactile reproductions of several art works, and a tactile path for independent navigation.

This tour was produced by CUAG, and designed with insights from members of Ottawa and Carleton’s blind and low vision community.

-

This audio description tour was written by Fiona Wright and recorded and edited by Nicole Bedford. Thank you to Rich Hillborn and Ludmilla Dubuisson for being the voices of the descriptions, and to artists Melanie Myers, Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona and Marigold Santos for their input.

Thank you to the members of Ottawa’s blind and low vision community who consulted on this tour in the early stages, as well as Carla Ayukawa. Thank you to Walter Zanetti for making the floor tracks and to Patrick Lacasse, who installed them.

Thank you to the curatorial team: Heather Igloliorte, Alice Ming Wai Jim, Anna Khimasia, Alexandra Kahsenni:io Nahwegahbow, Kosisochukwu Nnebe, Danielle Printup, Heather Anderson and Sandra Dyck. Artworks were generously loaned by the artists, private collectors, TD Bank Corporate Art Collection, Patel Brown, Cooper Cole, Norberg Hall and The Next Contemporary.

The exhibition is supported by The Joe Friday and Grant Jameson Contemporary Art Fund, The Reesa Greenberg Digital Initiatives Fund and The Mame Jackson Experiential Learning Fund.

-

Missing episodes?

-

This chapter describes a pastel on paper drawing titled Aujourd’hui l’echo de l’orage resonne by Rita Letendre, created in 1982, and measuring 47 by 67 cm. It is one and a half minutes long.

Can you feel a storm after it passes? Maybe in the smell of the air, or the temperature change. In Aujourd’hui l’echo de l’orage resonne, or “today the echo of the storm resounds,” Rita Letendre focuses on sounds and reverberations. She has used pastel, a chalky pigmented material, to create an abstract composition of horizontal bands of vivid colour, blurring or almost vibrating as they transition upwards from rich blue to yellow to pale green to orange to red to black to blue and then back to red. Is her inspiration the sky after a storm, or is it the artist reflecting on the aftereffects of a more personal, emotional storm? As she has written, “My paintings are completely emotional, full of hair-trigger intensity. Through them, I challenge space and time. I paint freedom, escape from the here and now, from the mundane…The world isn’t only what we see or what we experience.”

What are the textures or colours you attribute to emotions, both intense and tranquil?

You’re done the tour now! Turn right and follow the path to the bottom of the stairs, where you began. Thank you for joining us.

-

This chapter is the text written by curator Alice Ming Wai Jim. It is two minutes long.

Alice writes:

Marigolds thrive in the arid climates of Marigold Santos’s desert landscape paintings, one of which appears in the background of her studio depicted in the ink drawing shroud (arid interior I). The scene also affords us a glimpse of the artist’s take on the asuang (aswang), a traditionally terrifying shapeshifting creature of Filipino folklore.

Multiple configurations of this powerful, amorphous being populate Santos’s drawings and ceramics. Her reimagined asuang figures appear in numerous poses and positions — their shrouds at times made of thick dark masses, mystical woven textiles or braided voluminous hair, or exchanged for largebrimmed

veiled hats of different styles.The asuang mythology arose from the Babaylan — pillars of society as shamans and healers in pre-colonial Philippines — whose meaning and purpose were inverted by the Spanish colonizers. Reconfigured again, Santos’s asuang figure is hybrid in state and status, negotiating strata and longing, becoming land; these are not uncommon preoccupations today, during eras of migration and diaspora.

The blemishes or ink spots, or perhaps striae or scars, all over their bodies are more than skin deep. They tell stories, the narratives that make a life legible to oneself and to others. A form of permanent body adornment, tattooing was a prevalent cultural practice passed down in all ethnic groups of the Philippine Islands before they were colonized in the sixteenth century.

Super enlarged tattoo motifs of the artist’s design monumentalize this living art form as a cutaneous archive of ancestral knowledge that Filipinos are reviving today as a vibrant, decolonial practice.

Please move to the next stop. Turn right and follow the path for 4 metres. Then turn right and continue for 7 and a half metres. The drawing is on your left. This is the last stop of the tour.

-

This chapter features an interview with artist Marigold Santos. It is two and a half minutes long.

Hi Marigold, what is the inspiration or story behind your work in Drawing on Our History?

The works in this exhibition come from various moments in my practice from the last 5 years or so. They range in material and application, from works on paper to ceramics, paintings, and includes my tattoo practice, which is another form of mark making and drawing for me. This particular collection of works reflect on, and speak of, the body, embodiment of experience, self-hood, empowerment, and diaspora. The imagery consists of figures reconfigured from folklore, objects pulled from sensorial memories like touch, taste, and smell, and textures and patterns that come from my heritage and the landscape of my childhood.

Why do you choose to use Tagalog in some of the titles of your work?

My family immigrated to Canada in the late 80’s and I was just a child. I spoke Tagalog and did not understand English. We learned how to speak English very quickly, but my siblings and I stopped speaking our mother tongue in and outside of the home from that point on. Even though I can understand it quite fluently, I have difficulty in speaking it. Titling my work in Tagalog is a way for me to return to and honor my mother tongue in fragments. It is also a way for my work to reach folks who do understand Tagalog, and to create entry points into the work for them.

Why are you drawn towards being an artist?

Making art for me, has always been about communicating something – whether it is communicating something I am curious about, asking questions of, researching, or experimenting with, communicating is the undercurrent for me. I communicate through my work, and I think through my work. I also transform and evolve as a person through my work. My art practice is a way for me to continue to critically ask questions and make joy.

Go to the next chapter to hear the curatorial label for Santos’s work.

-

This chapter describes the ink drawing shroud (buntis na erotica) 1, made in 2021 and measuring 33 x 25 cm. long. It is a minute and a half long.

Two female figures dance together, each draped in a delicate, transparent cloth, or shroud. Their bodies mirror each other: the back of one hand is posed on one hip and the other hand is raised in the hair, bringing the shroud up along with it. They each step one foot towards each other, bringing them closer, almost intimately, together. Though the different elements of their bodies: breasts, swollen bellies and arms, are visible, their faces remain completely obscured by the shroud and by the splotches of ink that dot their whole bodies. The use of the veil teases us by hiding and revealing the dancers’ bodies, perhaps apt as the title of the artwork “buntis na erotica” means “pregnant erotica” in Tagalog. With no background, the attention is focused wholly on these women’s gestures and powerful bodies.

Go to the next chapter to hear Santos talk about her artwork.

-

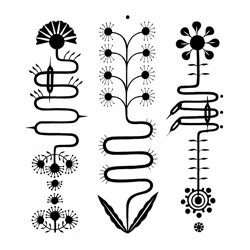

This chapter describes flower abstraction (elongated) 1, 2, 3 by Marigold Santos, made in 2022 and measuring four metres high. There is a tactile version of this drawing. It is labeled “6.” This chapter is a minute and half long.

In this artwork, Marigold created an enlarged vinyl version of a black drawing of three imagined flowers. They snake up the wall of the gallery vertically, reaching the level of the balcony above. In the tactile version of this drawing, you can feel the stems, petals and leaves. Each flower has at least three distinct parts, bottom, middle and top, and the stems zig zag in different sections, before separating off into small blooms of various shapes and sizes. The designs have very bold linework and are very stylized. The flowers appear to be surreal or otherworldly.

Santos is also a tattoo artist, and these black graphics recall a flash sheet, which tattoo artists use to display pre-designed creations. There are four flash sheets in this installation by Santos, and they are ink drawings on paper. They have multiple designs composed on one sheet. Which flowers do you think inspired this design? Though they are rendered in black, can you imagine them with colours? Can you imagine these designs tattooed on skin? What is the relationship between the large flower designs and the smaller flash drawings?

Go to the next chapter to hear about another work by Santos, hung on the wall to your left.

-

Marigold Santos is a Filipino-Canadian artist based in Calgary, and was invited to be part of the exhibition by Alice Ming Wai Jim, a curator and art historian at Concordia University in Montreal. You can hear her written reflection on Marigold’s artwork in Chapter 36. This chapter will give an overall description of Marigold’s installation, and the next two chapters will describe specific works within the installation. Then you’ll hear from Marigold herself. This chapter is a minute long.

Marigold’s installation is in a corner of the High Gallery, close to one of the gallery’s exits. The ceilings here are 6 metres high and you might hear visitors on the floor above, as the balcony stretches out into the space above you.

The largest part of this installation is a black floral design made of vinyl and applied directly to the gallery wall, 4 metres high. It is 4 and a half metres in front of you. There are also nine other works hung on the wall, some quite dark that were drawn in charcoal and pastel on paper, and others done with ink on paper. There is also one painting on canvas, as well as four tall square display cases with seven small ceramic pieces.

Go to the next chapter for information on Santos’s individual works.

-

This chapter is the text written by Mckenzie Holbrook for Glade and House. It is a minute long.

With its rhythmic brushstrokes and monumental trees, Glade and House demonstrates Emily Carr’s loose, expressive approach to painting on paper, in keeping with the large scale of the environment on British Columbia’s West Coast. The warm ochre tones suggest late summer or early autumn, painted with oil paints thinned with gasoline, which Carr valued for its economy and portability when working outside. Carr’s sweeping brush strokes emphasize the majestic trees, while the stumps in the foreground that line the path to the house at the centre of the composition, remind us of the giants that have been felled.

Please move to the next stop. Turn to the right and continue along this wall for 5 and a half metres.

-

This chapter describes Glade and House by Emily Carr, created in 1945, and measuring 89 by 61 cm. It is a minute long.

In this scene, tall trees dwarf a simple box cabin, built on the edge of a cleared section of the forest. The clearing, or glade, has been painted in muddy yellows, and is dotted with short black tree trunks. At this time, Carr, the renowned West Coast painter, used a thinned oil paint that had a consistency of cream. The brown paper underneath peaks out between the softly arched brushstrokes of varied greens she has used to depict the branches of the trees or the blue of the sky. These expressive gestures attempt to capture the aliveness of this scene, though it seems a stark commentary on human impact on the land. Though the cabin, and its invisible owner inside, seems enveloped by the trees, who knows how long it will be before they become stumps? What future is the owner of the cabin pondering as they stand looking out of those two tiny windows, taking in the smells of the air and trees all around them.

To hear more about this work, play the next track. Or move to the next stop. Turn to the right and continue along this wall for 5 and a half metres.

-

This chapter is the text written by Danielle Printup for Study for Cradle. It is a minute long.

A prominent multidisciplinary artist based in Southern Alberta, Faye HeavyShield is a member of the Kainai (Blood) Nation, which is part of the Blackfoot Confederacy. She has worked across media for over thirty years, often using a minimalist aesthetic approach to engage with embodied understandings of land, place and community.

This drawing, titled Study for Cradle, was made to draft the design for a three-dimensional sculptural work she later made using cotton, acrylic paint, and grass. It exemplifies HeavyShield’s ability to use minimal forms effectively, evoking a child’s presence with subtlety and power.

Move to the next stop. Continue on the path directly behind you, for 5 metres, crossing the gallery. The drawing is in front of you.

-

This chapter describes Study for “Cradle” by Faye HeavyShield, created in 1992, and measuring 61 by 47 cm. There is a tactile version of this drawing. It is labeled “5.” This chapter is one minute long.

In this graphite drawing, the artist has sketched out a baby’s garment, similar to a blanket with a peaked hood. Though the hood is up and the garment is filled out as if there is a little body inside, the face opening is dark. HeavyShield has layered dark pencil markings so that it creates the effect of a deep, cavernous void inside. Surrounding the form is a long triangular shape in soft pencil marks, almost like a shadow. The fabric is unpatterned, a simple white. The title “Cradle” perhaps refers to a cradle board, made and used by Indigenous peoples to protect and hold babies on their mother’s back.

To hear more about this work, play the next track. Or move to the next stop. Continue on the path directly behind you, for 5 metres, crossing the gallery. The drawing is in front of you.

-

This chapter is the text written by curator Sandra Dyck. It is two minutes long.

Sandra writes:

The groundbreaking American writer Audre Lorde famously described herself as “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet.” Lorde rejected external definitions of her identity that singled out, or marginalized, any one of these categories. Her poetry, she said, “comes from the intersection of me and my worlds.”

These questions of the part and the whole, of identity and belonging, are central to the work that Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona made for Drawing on Our History. Born in Qamani’tuaq — or Baker, as she calls it — to an Inuk father and a white mother, Kabloona has long lived away from the community. All her life, as she writes on these drawings, she has been asked, “What are you?” “Where do you belong?”

Kabloona belongs to making — to drawing, sewing, printmaking, knitting and building clay pots by hand. She belongs to the objects depicted in these drawings — sharp ulus with handles of wood or antler; a stone kudlik; a beaded sealskin marnguti that holds kudlik wicks; spherical ornaments made from ptarmigan gullets called puvviat — and to the creative acts that give rise to them. She belongs to her family tree, whose branches reach west to California and north to Inuit Nunangat.

Kabloona also belongs to the places she’s made home — Baker, Iqaluit, Ottawa. She belongs to the old stories she heard from her dad when she was a child. She belongs to the extraordinary legacy of visual culture inherited from Qamani’tuaq artists including Victoria Mamnguqsualuk (her grandmother), Jessie Oonark (her great-grandmother) and Luke Anguhadluq. Kabloona’s work comes from her intersection with all these worlds, and many more.

Please move to the next stop, which is in the High Gallery, or small arm of the “L.” Follow the path straight for 13 and a half metres. Then turn left and continue for 3 and a half metres. You are in the High Gallery now, with a 6 metre high ceiling. The drawing is on your left.

-

This chapter features an interview with artist Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona. It is a minute long.

Hi Gayle, what is the inspiration or story behind your work in Drawing on Our History?

I chose to share a personal reflection of my identity in my works for Drawing on Our History. Figuring out my place in the world has taken a lot of work. I wanted to show that even though I’m “half Inuk and half white” the people I identify with and who have also claimed me back are Inuit. I live in the duality of being an Inuit person and also being “half”.

Why do you choose to use of Inuktitut in some of the titles of your work?

I choose Inuktitut words for the titles of some of my works and English for others to represent my background in the middle of two cultures and my language learning journey. Friends and family help me name the Inuktitut pieces: teaching me and bringing me closer to those people.

Why are you drawn towards being an artist?

I like the idea of sharing my experiences and finding connections with other people. I think art gives my life deeper meaning and fulfillment. Also, my brain is constantly busy with creative projects and I’m the type of person who needs to keep their hands busy.

Go to the next chapter to hear the curatorial label for Kabloona’s work.

-

This chapter describes Ilakka by Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona, made in 2023 and measuring 35 cm high and 20 cm wide at the base and 12 cm wide at the top. It is a minute and a half long.

Behind you and to your left, one metre away, there is a display case with three vessels of varying sizes. Ilakka is the largest! 35 cm high, if you were to run your hands up the sides from bottom to top, your hands would go out and in, out and in, four times, with the curves growing progressively small as you reached the top. They are slightly irregular, and the exterior has not been glazed, so the reddish-brown clay feels dry and slightly rough. Instead of an overall glaze, Kabloona dipped her fingertip in white liquid clay and pressed it on the vessel while still wet, making dots all the way around, top to bottom. There must be hundreds! Each dot has then been turned into a face using tiny black brushstrokes: two eyebrows, two eyes, two dots for a nose and mouth. The variations of the brushstrokes change the identical faces into an array of expressions: smiling, frowning, stern. To top it off, each face is encircled with small red dots, creating the bright ruff of a parka hood. Kabloona’s use of her own biometrics is a way of literally imprinting herself, and all who came before her, on this object. This is echoed in the title’s translation: “my extended family.”

Go to the next chapter to hear Kabloona talk about her artwork.

-

This chapter describes a series of six drawings entitled You should be a part of us by Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona, made in 2023. Each drawing is on a horizontal piece of paper measuring 25 x 35 cm. There is a tactile version of part of this drawing. It is labeled “4.” This chapter is two minutes long.

There are six black ink drawings in Kabloona’s series “You should be a part of us,” hung in a row on the gallery wall. In each, bubble letters of text in both Inuktitut and English appear above and below a line drawing of an object from the artist’s home.

As you progress along the drawings, it reads: When I was growing up, people asked “What are you?” that said “you don’t belong (you’re not part of us.)” In Nunavut, Inuit asked, “Inuugaviit?” that said “Do you belong with us?” (you should be a part of us).

The drawings are of objects used in everyday Inuit life. In the first drawing there is a collection of ulus, or curved women’s knives, used for cooking and sewing. Kabloona has shown the texture of the antler handles using wavy vertical lines. Her qulliq, a gift from her sister, is a stone lamp shaped like a semi-circle. The smoothness of the stone is contrasted with a knobbly texture of a taqqut, a stick made of willow root for adjusting the flames at the base of it. The wick for a quilliq is typically arctic cotton, dried moss and willow fluff. In one drawing, her hands pick apart this wick material, readying it for the qulliq. In another, she threads a needle. Her fingers and wrists have tattoos of fine black lines. This final drawing in the series has the tactile version. Feel the patterns of her tattoos, and the weight she gives the lettering. How do the Inuktitut syllabics feel in comparison to the English letters?

Go to the next chapter to hear about another work by Kabloona.

-

Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona is an Inuk artist based in Ottawa, and was invited to be part of the exhibition by Sandra Dyck, Director of Carleton University Art Gallery. You can hear her written reflection on Kabloona’s artwork in Chapter 27. This chapter will give an overall description of the installation, and the next two chapter will describe two specific works. Then you’ll hear from Kabloona herself. This chapter is thirty seconds long.

Along the wall, there are six framed black and white drawings of objects from Kabloona’s home. There are also three vases in a display case. This section of the gallery is close to the stairs where you first came in, between two of the black floating walls.

Go to the next chapter for information on Kabloona’s individual works.

-

This chapter describes Birds Carry the Sun to Birdland by Lucy Qinnuayuak, created in 1977, and measuring 38 by 47 cm. There is a tactile version of this drawing. It is labeled “3.” This chapter is one and a half minutes long.

In this work, the sun is depicted as a charmingly irregular-shaped orange circle, held aloft in a yellow-green sky by nine birds. The colours are done with crayon, but the sun’s face is drawn in black ink, feminine eyes encircled by eyelashes gaze out at us, and her small mouth tilts to the right in a half smile. Her face has dotted lines across the cheeks, nose and forehead, in familiar designs of Inuit women’s tattoos. These black dotted lines also appear on the red, blue, green and black birds.

Can feel the dotted patterns on the tactile version?

Tattoos were opposed by Christian missionaries in the north for hundreds of years, something that Qinnuayuak, who lived between 1915 and 1982, would have experienced. They have had a revival recently, however, with many young Inuit women learning the techniques and designs of their ancestors. The directions of the birds, pointing east, west and north, create a symmetry to the drawings, and the black dots create kinship between the fowl and their precious cargo.

Please move to the next stop, along the wall for 3 and a half metres, and turn to the left.

-

This chapter is the text written by Mckenzie Holbrook for Summer Landscape. It is a minute long.

A founding member of the 1950s Toronto collective Painters Eleven, Kazuo Nakamura created artworks inspired by the New York abstract expressionist movement, as well as more figurative works. Nakamura viewed abstraction as a means to investigate and explore different modes of perceiving the natural world.

The gestural, minimal brush strokes and muted colours of Summer Landscape bleed into the white expanse of the paper. As an artist interested in scientific ways of knowing, Nakamura portrayed the natural world as he saw it, unveiling the many ways beauty can be perceived. Here, Nakamura leaves viewers to fill in details; his loose gestural approach lends a moody, cool atmosphere to Summer Landscape.

Please move to the next stop. Continue along this wall for 8 and a half metres. The drawing is on your left.

-

This chapter describes Summer Landscape by Kazuo Nakamura, created in 1954, and measuring 39 by 57 cm. It is a minute long.

This drawing is hung above another landscape watercolour drawing by John Esnor. In Nakamura’s drawing, the artist used staccato brushstrokes of watercolour pigments to create a minimal, almost abstract, landscape scene of two trees standing on the left in a grassy field. Bright greens, vivid teal-tinged blues and hints of ochre are used to depict the leaves, grasses and smaller trees in the background. Water makes the colourful brushstrokes feather out, as it soaks into the thick paper. It mimics the haze of summer heat that can sometimes blur your perception. Was the artist standing in this field while he painted it, the short and messy brushstrokes reflecting his rush to capture the colours and light of this view? Much of the page is left unfilled, and there are no details about the specific location.

To hear more about this work, play the next track. Or move to the next stop. Continue along this wall for 8 and a half metres. The drawing is on your left.

- Show more